● From our sister site, TheSportsExaminer.com ●

This has been a tough week for American track & field fans, with the passing of two great stars: 1976 Olympic long jump champion Arnie Robinson on Tuesday (1st) and 1960 Olympic decathlon gold medalist Rafer Johnson on Wednesday (2nd).

¶

If I’m laden at all

I’m laden with sadness

That everyone’s heart

Isn’t filled with the gladness

Of love for one another

It’s a long, long road

From which there is no return

While we’re on the way to there

Why not share

~ from “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” by The Hollies (1969)

We often honor our cultural icons by shortening their names to one word.

Babe. Bird. Elvis. Elton. Rafer.

There was only one Rafer Johnson, but we should hope for many more. Tall, lean and muscular, he looked like he was ready to come back to the decathlon decades after his gold-medal performance in Rome in 1960.

When he walked into a room, all eyes looked his way. Everyone stood a little straighter. Voices were lowered. Decorum was suddenly in vogue. And to those who whispered, “Who is that?” the reply was a hushed, “Rafer.”

Until he broke out his winning smile and extended his hand to the first person he met, and if he didn’t know them already, he said. “Hi, I’m Rafer Johnson.”

Much of Rafer’s story is well known, from his modest start in Texas, move to California in 1945 and the start of his brilliant athletic career at Kingsburg Joint Union High School in Fresno County. But after 60 years, just how great Rafer was is largely unappreciated.

As a freshman at UCLA, he won the Pan American Games decathlon in March, then set his first world record in the decathlon at age 20 in June of 1955, scoring 7,985 points on the then-current scoring tables at the Central California AAU Championships to erase Bob Mathias’s 1952 total of 7,887.

(There has been considerable anxiety over Rafer’s age. Many sources – for many years – carried his birthdate as 18 August 1935, but his family confirmed he was born in 1934, making him 86 when he passed on Wednesday. Our original posting had him as 85, but has been corrected.)

Competing under the direction of UCLA coach Ducky Drake, he led UCLA to the 1956 NCAA track & field championship – its first in the sport – with 16 points from runner-up finishes in the high hurdles and long jump. He made the Olympic team in the long jump and just missed making the hurdles final at the Final Trials at the Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles. At the separate Olympic Trials for the decathlon, he won by 191 over Milt Campbell with 7,755 despite injuring a knee during the discus.

He had a lot more trouble with the knee at the Melbourne Games and had to abandon the long jump altogether, and finished second to Campbell, 7,937 to 7,587.

There were more injuries in 1957, but by 1958, he was back on the track – as well as being Student Body President at UCLA – and emerged as the world’s best decathlete. His 1955 world mark had been broken by Soviet Vasiliy Kuznetsov in May (8,014), but Rafer took it back – head to head – at the USA vs. USSR dual before 75,000 spectators in Moscow, scoring 8,302 to 7,865 for Kuznetsov.

He was a starter on the 1958-59 UCLA basketball team under John Wooden, scoring 8.2 points a game for a 16-9 Bruin squad and despite never having played college football, was selected by the Los Angeles Rams in the 28th round of the 1959 NFL Draft.

But his focus was clearly on the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. Long-time track & field statistician Barry Schreiber notes that he was in a serious auto accident in 1959, resulting in a significant back injury.

He could barely jog in the early days of 1960, but by April he was sprinting again and training with a new Bruin, Taiwanese C.K. Yang. By the time of the Olympic Trials in July, Johnson smashed Kuznetsov’s 1959 world record of 8,357 by scoring 8,683, ahead of Yang – a guest competitor – who scored 8,426, also better than the old record.

Their duel in Rome is well known, with Johnson winning by staying with Yang during the 1,500 m – and finishing with a lifetime best of 4:49.7 – and then collapsing with his friend after the finish line. Rafer won by just 8,392-8,334.

That’s where his track career ended and Rafer’s incredible life story began. He appeared in several movies, was a sports anchor at KNBC-TV in Los Angeles, worked for the Peace Corps and was with Sen. Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1968 when he was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan, holding the assailant down with Rams tackle Rosey Grier and actually taking his gun away.

Soon after, Johnson was invited to go to Chicago and witness the beginnings of what became the Special Olympics, organized by Kennedy’s sister, Eunice Shriver. Rafer came back and helped found Special Olympics California and raised the profile of a fledgling organization into one of the most important support programs for the intellectually challenged worldwide.

In 1971, he joined Continental Telephone as a Vice President, for community and government relations, and its personnel departments, in 42 states, and remained there until retirement. At one time the third-largest independent telco in the country, ConTel was later acquired by GTE, which itself is part of today’s Verizon conglomerate.

Johnson was also never far from the Olympic Movement. He was a key member of the 1970s President’s Commission on Olympic Sports, which led directly to the Amateur Sports Act of 1978 (now the Ted Stevens Olympic and Amateur Sports Act), which turned control of the U.S. Olympic efforts to the United States Olympic Committee and largely ended the war for athlete control by the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and NCAA.

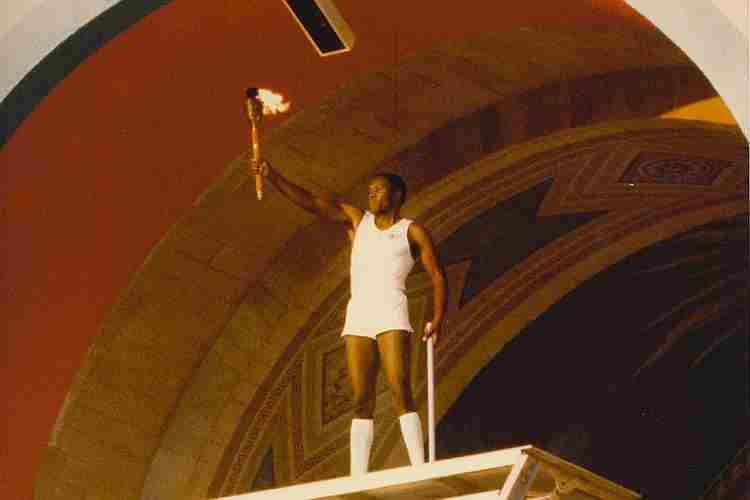

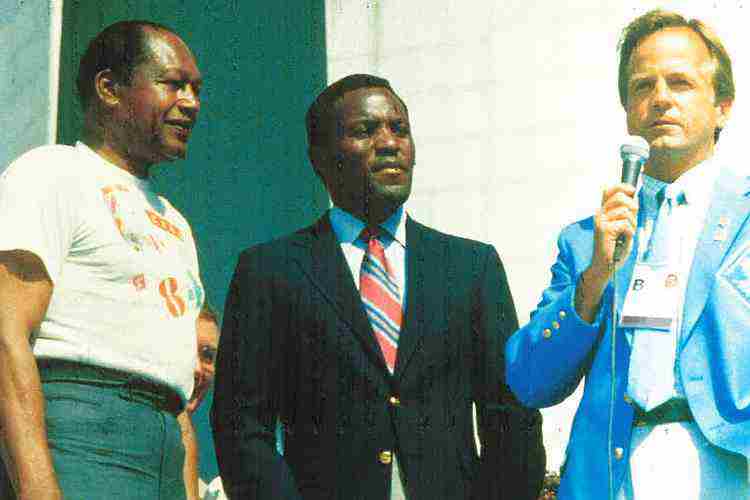

He was a charter member of the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee’s Board of Directors and played a key role in the selection and confirmation of Peter Ueberroth as its President in 1979. And, of course, he was the final torchbearer at the Opening Ceremony of the 1984 Games, ascending a rising, narrow staircase – despite a charley horse in one leg – and lighting the Olympic flame once more in the Coliseum.

His work with Special Olympics was crowned by having its World Games return to Los Angeles in 2015, where Rafer marched in with one of the teams during that Opening Ceremony, again at the Coliseum.

And if he was in Los Angeles, he never missed a UCLA home track & field meet at Drake Stadium – named for his coach – and the track was dedicated to he and wife Betsy in 2019.

Rafer slowed considerably after a stroke in 2018, and he passed with his family in his Sherman Oaks home early Wednesday morning.

Of his friend and a man who changed his life, Ueberroth said, “He’s one of those rare individuals that thinks about the other person first, and basically helped everybody that he has touched in his lifetime.”

His 1960 Olympic teammate, swimmer Donna de Varona – then just 13! – remembered her lifelong friend thus:

“He had an elegance about him. He was as strong as he was gentle.

“He was humble, so humble. I recall asking him why he was so devoted to the Special Olympics movement. He told me, in many ways he identified with the struggles of those he championed.

“As the founder of the Special Olympics organization in Southern California, Rafer was unstoppable. Financing the World Games was a full-time job and Rafer was not going to fail. He never missed meetings, outings or interviews. During the 2015 Games Rafer, at age 81, seemed as if he had boundless energy as he raced from one venue to another. He was happiest when mingling with the Special Olympic competitors and their families.”

His UCLA track & field teammate Stan King, also a fraternity brother at UCLA and a long-time track & field official in Southern California, stayed close with Rafer over the decades. He added:

“If anyone, during our lifetime, has made an indelible impact on all peoples, it has been Rafer. A humble man with a charming smile and a caring heart, he made a profound difference in this world. His accomplishments were incomparable, but his integrity and kindness were his trademarks.”

In contrast to today’s coarse, discordant, angry public culture, Rafer demonstrated again and again a powerful force of presence that made dignity, patience and calm the tools that can solve problems of all kinds. He was one of a kind and irreplaceable. But we need many more Rafers and we need them now.

● For an excellent summary of Rafer’s life and achievements, please see the family’s announcement following his passing, masterfully constructed by longtime family friend Michael Roth, the communications chief for the Anschutz Entertainment Group.

● UCLA’s first tribute to one of its true icons is here. There will be more.

● The LA84 Foundation, of which Johnson was a founding Board member, saluted him with an exhibition earlier this year, which can be viewed in part online here.

¶

On Monday, the track & field world lost another champion, long jumper Arnie Robinson, who lost his battle with a brain tumor on Tuesday morning, aged 72.

His quiet demeanor hid a steely determination to be the best in the world, as his competitors well knew. He was a San Diego legend, attending Morse High School, San Diego Mesa Community College and then San Diego State, where he was the 1970 NCAA Champion.

Robinson was the finest long jumper of the mid-1970s, winning the U.S. national title in 1971-72-1975-76-77-78, earning a gold medal at the 1971 Pan American Games and the silver in 1975 and two Olympic medals: a bronze in 1972 in Munich and the gold in Montreal in 1976. His lifetime best of 8.35 m (27-4 3/4) came under the greatest pressure meet of all: the 1976 Olympic Games.

Lanky, even frail-looking at 6-2 and just 165 pounds, Robinson developed excellent speed at the takeoff point and almost always fell forward, making the most of his jumps.

Because he was so quiet, he was widely overlooked by sponsors and went into construction after his athletic career wound down. In 1982, he began coaching at Mesa and became a professor in Health and Exercise Science, a position he maintained until retirement. Robinson retired from coaching and teaching in 2010 as both a teacher and track coach; his 1998 women’s team won the California Community College State Championship.

In a 2018 feature in the San Diego Union-Tribune, his start in the sport was remembered:

“‘The way it started, he would train himself,’ recalled his sister, Carolyn Johnson. ‘I remember one day specifically, he took an old mattress our mom had set out. He put it in the driveway by the garage. That’s how he started the long jump. I thought it was crazy.’”

What was Robinson about? The story noted:

“The more you learn about the 70-year-old, the more you come to understand that he’s a find-a-way guy. When he didn’t have enough money to buy a house near his childhood neighborhood, he built one from the ground up. When he picked up bowling, he polished his game in a Lemon Grove league until he recorded a 230 average with one of those devastating hooks the pros deliver.

“When youth track in San Diego lacked a caretaker, he chalked the lines for the lanes himself. When the youngest in the sport needed timing equipment, [son] Paul Robinson said his father spent more than $35,000 of his own money to make it happen.”

Robinson was nearly killed in a 2000 auto accident, but recovered. He was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2005 and was expected to live just another six months, but he only succumbed some 15 years later. Family friend Brian Kyle said at the time:

“You can’t be attached to someone like Arnie and be a quitter.”

~ Rich Perelman

Be the first to comment